Diary of a Madman Review by Natalie Lifson

You walk into an office building. The same office building you walk into every day. You take a seat at your desk. You look around at all the familiar faces. Nobody’s looking at you. Nobody’s ever looking at you. You don’t matter here. You don’t belong here. You could be someone important in another life. Someone worth glancing up at as you enter the room. Someone worth loving. She doesn’t want you and she never will. You’re alone in the world. You’re nothing. Insignificant. It’s enough to drive a person mad.

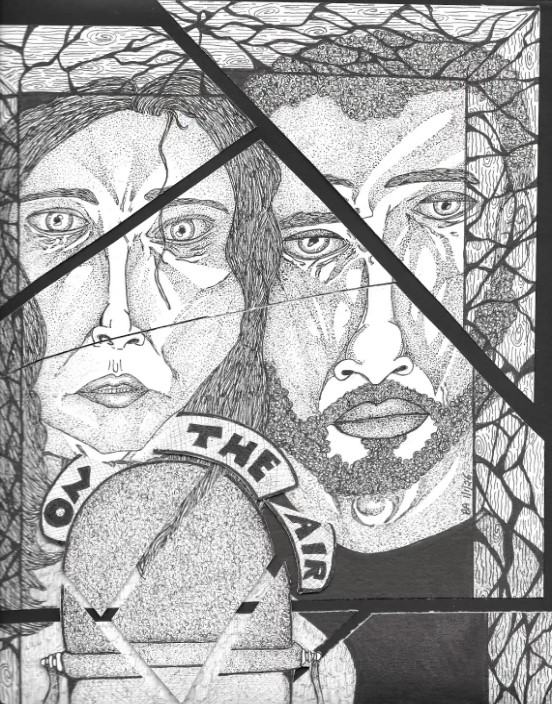

Diary of a Madman , a one man show adapted by actor Ilia Volok and director Eugene Lazarev from a story of the same title by Russian author Nikolai Gogol, explores the psyche of a man, Poprischin, who feels so dissatisfied with his own role in life that he gradually descends into a sort of madness characterized by paranoia and grandiosity.

Diary of a Madman , a one man show adapted by actor Ilia Volok and director Eugene Lazarev from a story of the same title by Russian author Nikolai Gogol, explores the psyche of a man, Poprischin, who feels so dissatisfied with his own role in life that he gradually descends into a sort of madness characterized by paranoia and grandiosity.

Throughout the brilliant painting that is Volok’s performance, every twitch of his face, every jerk of a limb, is another artfully placed brushstroke on the captivating emotional landscape of Poprischin, the civil servant who just wants to be noticed, who just wants to matter in a world that seems to have completely discarded him.

Throughout the brilliant painting that is Volok’s performance, every twitch of his face, every jerk of a limb, is another artfully placed brushstroke on the captivating emotional landscape of Poprischin, the civil servant who just wants to be noticed, who just wants to matter in a world that seems to have completely discarded him.

Even with a minimal set that consists only of a blank stage framed by two ladders, Volok manages to transport us into not only into the early 19th century, but into Poprischin’s rapidly declining mind. As Poprischin progressively loses touch with reality, as he determines that he is, in fact, the king of Spain, as he stalks Sophie, the woman he is in love with, Volok’s movements become jerky and over exaggerated. His eyes bug out as he shouts sentences that a sane person would utter at an ordinary volume. He pauses in the middle of sentences to breathe rapidly. His face contorts to display his dwindling internal conflict like an open book. It is so easy to forget that Volok is not, in fact, the elderly madman with a limp that he plays so skillfully. Likewise, Volok is so gifted at miming that suspension of disbelief becomes second nature. When Poprischin talks to a dog, the audience feels as if the dog is truly there. When Poprischin enters Sophie’s bedroom without permission and addresses her, the audience can almostbutnotquite see her out of the corner of our eyes.

Volok is particularly engrossing to watch in the moments in which madness utterly consumes Poprischin. A particularly riveting scene finds Poprischin ranting about women and the devil. As he shouts and stomps and lurches his body in different directions, the lights, designed by Ken Coughlin, bleed a dark red. This , Coughlin, Lazarev, and Volok alike seem to indicate, this is true madness.

While Diary of a Madman certainly keeps the audience on the edges of their seats throughout the entirety of the performance, the highlight of the show by far is the use of sound, as designed by David Marling, particularly when Poprischin discusses Sophie. When Poprischin as much as hands Sophie a handkerchief, he pauses where he stands, his movements become fluid, and he babbles on and on about the object of his obsession as music begins to play. In the background every time thoughts of her pop into his head, the song “Una Furtiva Lacrima,” sung by Izzy, plays in the background and dictates his bodily movements. “Una Furtiva Lacrima,” which is from the Italian opera L’elixir D’Amore and details the emotional experience of a man who uses a love potion on a woman who he had tried and failed to win the heart of, is a fitting song choice that flawlessly characterizes Poprischin’s manic passion in Diary of a Madman.

The raw emotion displayed by Volok in these moments, paired with Izzy’s voice in the background, is intoxicating and impossible to look away from.

In addition to being a powerful and entertaining piece of art, Diary of a Madman is a profound commentary on mental illness, homelessness, and empathy. Despite Poprischin’s madness, it is impossible for the audience not to empathize with his situation. Although his emotions are amplified, the experience of loneliness, of invisibility, is one that is universal. Poprischin begins just like any man; he is an average office worker with average job performance and an average life. He is someone that anyone could know, that anyone could be. He transforms from this universal character into a homeless madman claiming to be a king on the street, not dissimilar from people we walk quickly past on the street every day and avert our eyes from. Poprischin may be a figment of Gogol’s imagination, but truthfully, he could be anyone.

The production is extended through February 18 so there are still ample times to see this masterful work.

Leave a comment