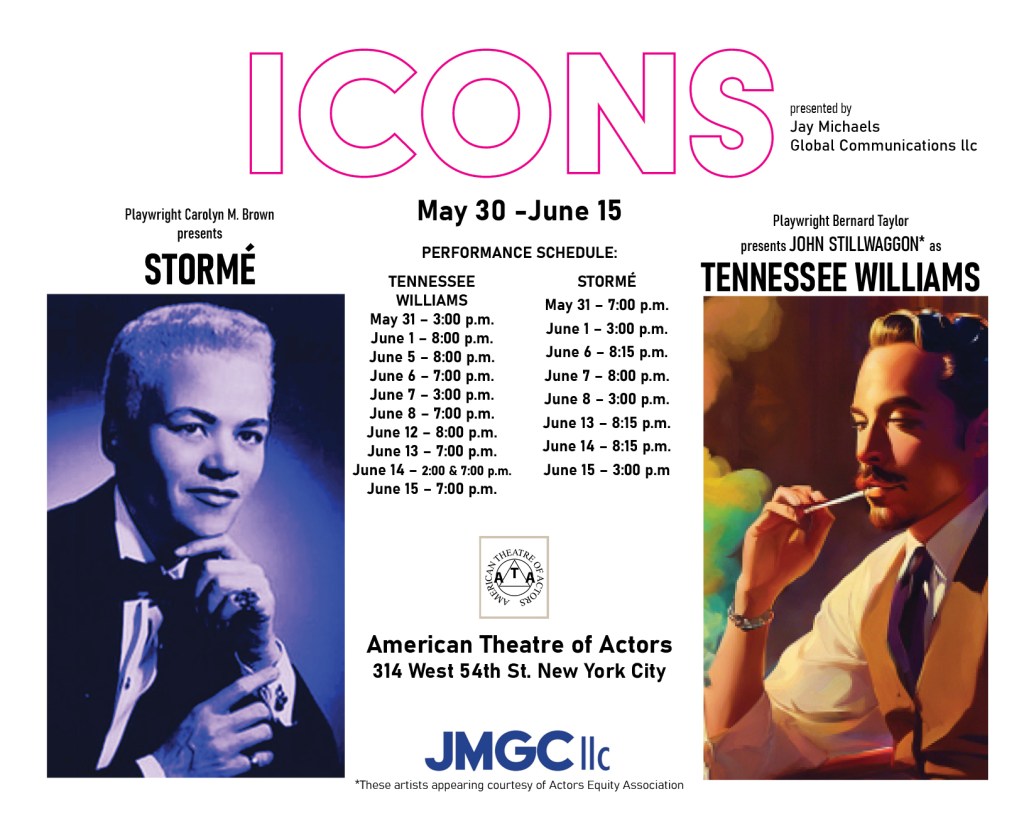

The intimate setting of the Sargent Theatre at the American Theatre of Actors is currently playing host to a unique theatrical endeavor: “Tennessee Williams: Portrait of a Gay Icon,” a one-man play starring John Stillwaggon as the legendary playwright. At the helm of this production is director Carolyn Dellinger, an Alaskan transplant with a diverse and impressive theatrical background. While her resume boasts a range of works, from Shakespearean classics to children’s touring productions, her approach to this particular piece promises a nuanced and deeply personal exploration of one of America’s most celebrated and complex literary figures.

Dellinger’s journey to this project, as she describes, has been a rich tapestry woven from various theatrical threads. Her experience running a touring theatre and her multifaceted roles as writer, director, and costumer showcase a deep-seated passion for bringing stories to life. This hands-on experience likely informs her directorial style, fostering a collaborative environment and a keen understanding of the practicalities of staging a compelling narrative, even in the intimate form of a one-person show.

What drew Dellinger to “Tennessee Williams: Portrait of a Gay Icon” appears to be a profound respect for both the playwright and the actor embodying him. She speaks with admiration for John Stillwaggon’s talent, his receptiveness to direction, and his remarkable memory, highlighting the collaborative synergy that has been crucial in building their portrayal of Williams. This emphasis on the actor-director relationship suggests a process built on trust and shared artistic vision, essential when navigating the complexities of a solo performance that demands both vulnerability and command.

Dellinger articulates a compelling rationale for why audiences today need to engage with the legacy of Tennessee Williams. For her, Williams is not just a brilliant writer who crafted deeply nuanced and emotionally resonant characters; he was also a man who bravely laid bare his soul on stage. She astutely observes that “when you write for the theatre, you are leaving a piece of your soul naked onstage,” and argues that Williams’ unflinching honesty, including his “ugly parts,” offers invaluable lessons for aspiring and established artists alike. This perspective suggests that Dellinger’s direction will likely delve beyond a mere biographical recitation, aiming to uncover the raw humanity that fueled Williams’ iconic works.

As a female director tackling the work of a playwright often lauded for his complex and unforgettable female characters, Dellinger offers a unique perspective on the “Tennessee Williams woman.” She astutely identifies the recurring theme of entrapment in his plays, attributing it to both societal expectations of the time and the experiences of the significant women in Williams’ own life. Dellinger connects this external confinement to Williams’ own feelings of being trapped, suggesting a deep empathy that allowed him to imbue his female characters with such profound humanity. Her interpretation of Blanche DuBois’ final moments in A Streetcar Named Desire – not as defeat, but as a triumph of maintaining dignity in an impossible situation – reveals a nuanced understanding of the strength and resilience that often underlies the apparent fragility of Williams’ heroines. This insight promises a direction that will likely illuminate the profound connection between Williams’ life experiences and the women he so vividly brought to life, a connection that Stillwaggon’s portrayal will undoubtedly explore through Williams’ own reflections in the play.

The play’s title, “Tennessee Williams: Portrait of a Gay Icon,” raises the question of how Dellinger intends to navigate this aspect of Williams’ identity, particularly given that he is often remembered more for his literary brilliance than his role in LGBTQ+ history. She acknowledges the script’s contribution in offering glimpses into the delicate balance Williams had to strike between survival in the Deep South and challenging societal norms. This suggests that Dellinger’s direction will subtly, yet powerfully, underscore the challenges and complexities of being a gay artist in a less accepting era, allowing audiences to appreciate this often-overlooked dimension of his legacy.

Dellinger clearly feels a significant sense of responsibility in presenting this work. Her hope is that audiences will leave the theatre not just with historical facts about Tennessee Williams, but with a visceral sense of having “got to know him as a person.” She eloquently uses the analogy of a late-night, heartfelt conversation to illustrate her goal: to create an intimate and revealing encounter with the playwright’s essence. This ambition points towards a direction that prioritizes authenticity and emotional connection, aiming to create a profound and lasting impression on the audience.

When asked who “needs” to see this play, Dellinger’s answer is direct and insightful: “Anyone who writes, or wishes to write, or wishes to better appreciate writers.” This highlights her belief in the play’s potential to offer valuable insights into the creative process, the courage required for artistic vulnerability, and the profound connection between an artist’s life and their work.

Looking ahead, Dellinger reveals her own burgeoning career as a playwright, transitioning from children’s theatre to more adult subject matter. This personal creative endeavor likely enhances her understanding of the playwright’s craft and informs her approach to directing Bernard Taylor’s work.

In “Tennessee Williams: Portrait of a Gay Icon,” under the thoughtful and experienced direction of Carolyn Dellinger, audiences at the American Theatre of Actors are invited to step beyond the iconic status and engage with the vulnerable, complex, and deeply human figure of Tennessee Williams. Dellinger’s vision promises not just a performance, but an intimate encounter with the soul of a literary giant, brought to life with sensitivity and insight.

Leave a comment